Link .. http://www.bigfootencounters.com/crea...

Animation is from Patterson sighting.

Please visit my website at http://www.YouRTubeNews.ning.com

The Story of Jacko

The story of Jacko – that of a small, apelike, young Sasquatch said to have been captured alive in the 1800s – is a piece of folklore that refuses to die, despite a superb investigative article published in 1975, co-authored by John Green and Sabina W. Sanderson.

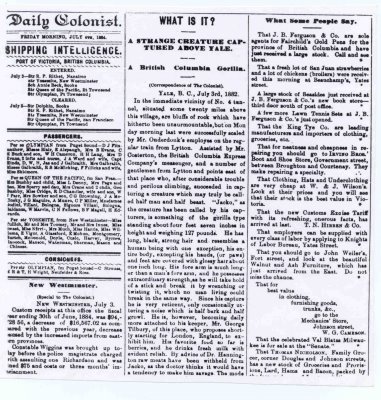

The investigation into the Jacko story did not began until decades later. During the 1950s, a news reporter named Brian McKelvie became interested in the then-current stories of the Sasquatch being carried by his local British Columbian papers. McKelvie searched for older reports. What he found was the Daily British Colonist July 4, 1884, article about Jacko. The account detailed the sighting of a smallish hairy creature (“something of the gorilla type”) supposedly seen and captured near Yale, British Columbia, on June 30, 1884, and housed in a local jail.

McKelvie shared the Jacko account with researchers John Green and René Dahinden. MeKelvie told them this was the only record of the event due to a fire that had destroyed other area newspapers of the time.

In 1958 John Green found and interviewed a man (August Castle) who remembered the Jacko talk of the time, but he said his parents did not take him to the jail to see the beast. Other senior citizens remembered the talk of the creature, but no one could produce any truly good evidence for or eyewitness accounts (other than the British Colonist story) of Jacko.

The story’s appearance in Ivan T. Sanderson’s 1961 Abominable Snowmen: Legend Come to Life propelled the Jacko incident into history. Other authors, including John Green, René Dahinden/Don Hunter, Grover Krantz, and John Napier, would follow. The story was repeated again and again.

John Green continued digging into story and finally discovered that microfilms of British Columbia newspapers from the 1880s existed at the University of British Columbia. Green then found two important articles that threw light on the whole affair.

The New Westminster, British Columbia, Mainland Guardianof July 9, 1884, mentioned the story and noted: “The ‘What Is It’ is the subject of conversation in town. How the story originated, and by whom, is hard for one to conjecture. Absurdity is written on the face of it. The fact of the matter is, that no such animal was caught, and how the Colonist was duped in such a manner, and by such a story, is strange.”

On July 11, 1884, the British Columbian carried the news that some 200 people had gone to the jail to view Jacko. But the “only wild man visible” was a man, who was humorously called the “governor of the goal [jail], who completely exhausted his patience” fielding the repeated inquiries from the crowd about the nonexistent creature.

As Green has pointed out, the Colonist never disputed its critics. Green (with Sanderson’s widow) wrote of the Jacko story as a piece of probable historical journalistic fiction in the article, “Alas, Poor Jacko,” in Pursuit published in 1975.

Unfortunately, a whole new generation of hominologists, Sasquatch searchers, and Bigfoot researchers are growing up thinking that the Jacko story is an ironclad cornerstone of the field, a foundation piece of history proving that Sasquatch are real. But in reality Jacko may have more to do with local rumors brought to the level of a news story that eventually evolved into a modern fable.

Loren Coleman © 2003

^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

That ends the retelling of this tale from my book, Bigfoot! The True Story of Apes in America (NY: Simon and Schuster, 2003), on pages 41-42.

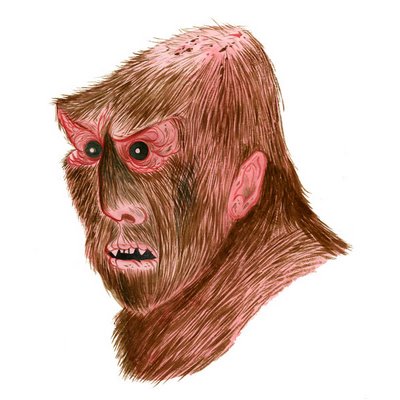

Artist Mordicai Sulk’s unique view of a young Sasquatch.

Some additional thoughts might be helpful to consider.

The complete description of this apparently newspaper cryptofiction creation, Jacko, is as follows: “Something of the gorilla type standing four feet seven inches in height and weighing 127. He has long, black, strong hair and resembles a human being with one exception, his entire body, excepting his hands, (or paws) and feet are covered with glossy hair about an inch long. His fore arm is much longer than a man’s fore arm.” (from “What Is It? A Strange Creature Captured Above Yale ~ A British Columbia Gorilla,” Victoria, British Columbia, Daily Colonist, July 4, 1884).

John Green’s 1978 book, Sasquatch: The Apes Among Us expresses his feeling that “it doesn’t look good for Jacko,” but people have uncritically reported the Jacko story, with elder citizens’ remembrances of the media attention to it, as if that is evidence for the reality of Jacko. Anyone re-researching this story should be aware that there are those who wish to continue to “believe” this journalistic tale tall. One part of their argument is that the media excitement of those times is justification for a factual basis in the creature, even though, of course, there is no direct correlation between those two elements of this hairy melodrama.

Other overblown claims have been made about how thoroughly the subject has been investigated.

For example, it has been widely disseminated, incorrectly, that Myra Shackley “did perhaps the most exhaustive effort in the search for Jacko.” Those writing such statements appear to have not read Shackley’s recycling of the news item and her brief paragraph following it. They do not seem to realize how illogical their comments are, for Shackley merely referenced and rehashed John Green’s early research.

Dr. Myra Shackley conducted remarkable and outstanding research on hominoids, but most of her work on Sasquatch was limited to a review of others’ findings. Her speciality was Eurasia. Here above she is shown in 1980, on “Arthur C. Clarke’s Mysterious World” television program.

For Bigfoot researchers to say that Shackley “actually found a resident by the name of August Castle whom confirmed the newspaper report,” belies the facts of the case. She did not.

The youthful newspaper editor John Green spent several years interviewing oldtimers in Western Canada about their earlier Sasquatch encounters.

The Castle interview was conducted in 1958, by Green, when Castle was 80 years old and when Shackley, living in England, would have been 13 years old! Shackley’s research into relict Neanderthal populations took her to Mongolia in 1969, when she was 29, not to British Columbia to do “exhaustive research” on Sasquatch.

Shackley abandoned her hominological research in the late 1980s, after she wrote Wildmen: Yeti, Sasquatch and the Neanderthal Enigma (London: Thames & Hudson, 1983). No doubt August Castle was deceased by the time her long-distance Sasquatch research began and her writings were published.

Few have commented on the use of the name “Jacko,” or that it was called a “gorilla,” so let me share some historical context notes on these aspects of the 1884 story.

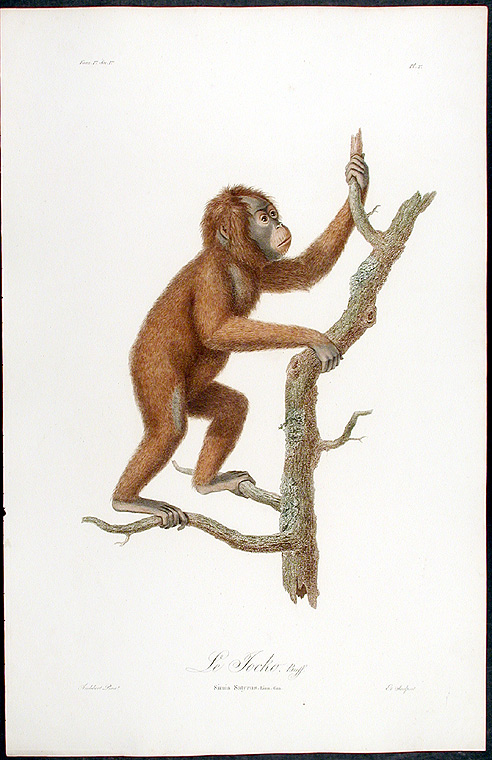

During the early days of finding great apes and talk of monkeys, there was a tendency to name them “Jocko,” or by corruption, “Jacko.”

One famed painting from France that appeared entitled Le Jocko, in the late 18th century speaks to how some primates were named “Jocko.” The painting below is by Jean-Baptiste Audebert (1759-1800), and is listed in auctions and libraries as Le Jocko / Simia Satyrus. The beautiful rare print is dated 1797 [-1800], and is from one of the greatest monographic work on mammals ever published, Histoire Naturelle des Singes, which appeared in only 138 published copies.

What species do you think it might have been?

For those that wish to tie the British Columbian “Jacko” with P. T. Barnum, it must be pointed out that the appearance of “Jocko” occurred from August 28, 1865 through September 2, 1865, at Barnum’s American Museum in New York City, fully 19 years before the news article was published of “Jacko’s capture” in Canada.

It appears that since 1849, a play involving a monkey-man role on Broadway was being performed in a pantomime called “Jocko.” Barnum merely provided a temporary setting for this famed play.

As the anthropologist Jane Goodall explained during a November 1, 2002 ABC radio interview:

In the show business, Jocko was an old friend and familiar who could stage his return in any guise he pleased, and be confident of a warm reception. The story of “Jocko or the Brazilian Ape’ involved a child and monkey in parallel roles, and the pantomime, first performed in Paris in 1825, was choreographed so that their movements offered mirror images. Jocko the ape has been adopted by an enlightened plantation owner. After being rescued from a killer serpent the plantation owner is determined to educate him. And Jocko repays the favour by rescuing the owner’s son from a shipwreck, then saving him in turn from the killer serpent. The plantation workers, not as enlightened as the boss, become suspicious of the ape and attack him. But he’s rescued again, and in the finale, Jocko and the child dance side by side, as adoptive brothers.

The idea that there was an ape in the family, supposedly so shocking to the Victorians, was evidently hugely enjoyable to popular theatre audiences who’d embraced it long before Darwin put his particular spin on it.

When the pantomime was recreated for New York audiences, it became less precious and sentimental, more acrobatic. And it set off a craze for burlesque imitations. Jocko, variously camped up, was soon making appearances in the minstrel shows as a character in his own right, a cult figure who could be relied upon to get the audience cracking up. He was the outsider who was on intimate terms with them, communicating through comic mime with expressions and gestures that became a well known code.

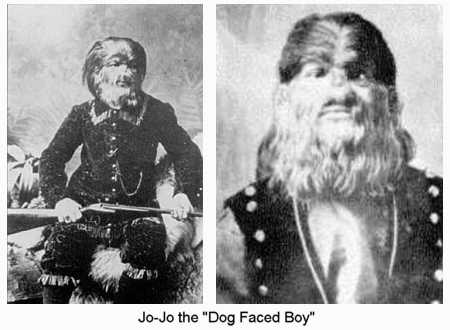

If things were not confusing enough, P. T. Barnum began “exhibiting” a Russian man in 1884, billed as “Jo Jo – The Dogfaced Boy.”

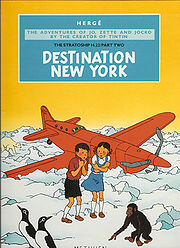

The use of the name “Jocko” to denote apes and monkeys continues into modern times. In the 20th century, The Adventures of Jo, Zette and Jocko (1936-1957) was a comic book (or bande dessinée) series created by the famed Hergé, the Belgian writer-artist Georges Prosper Remi (May 22, 1907 – March 3, 1983), who was best known for The Adventures of Tintin (1929-1983). The heroes of the series are two young children, brother and sister Jo and Zette Legrand and their pet monkey Jocko. The monkey Jocko sometimes appeared on the back covers of various editions of The Adventures of Tintin (one of the best of which was about the Yeti).

What of the use of the word “gorilla” in British Columbia in 1884?

In North America, at the end of the 19th century, the use of “gorilla” in article references (as I detailed in a Fortean Times column in 1997), is directly related to the media attention about gorillas whipped up by Du Chaillu’s sensationalistic travels in Africa and his book that came out in 1861.

Vernon Reynolds (in The Apes, 1967. p. 137) writes: “After (Du Chaillu’s) trip, which lasted from 1856 to 1859, Du Chaillu returned to the United States, where he received widespread acclaim.”

In 1863, another famous gorilla/travel book was published, written by American explorer Winwood Reade, after he spent five months in gorilla country. Nineteenth century articles about “strange creatures” – whether real or imagined – often thus labeled them as “gorillas.”

While a parallel tribe of wild men and women, often hairy and uncivilized, in the Pacific Northwest, living harmoniously and contemporarily with the Indians, was taken somewhat for granted by the First Nations people, it would not be until the 1920s when J. W. Burns introduced “Sasquatch” and in 1958 when Andrew Genzoli disseminated “Bigfoot” via a national media, that non-Indians would more widely begin to acknowledge the hairy giants of the woods.

If “Jacko” had been real and shown in sideshows, zoos, or at universities, the entire history of anthropology and zoology in the Americas would be different.

But one journalistic tall tale does not undermine hundreds of years of Native traditions, folklore, and sightings that point to a reality-based foundation of true apes in North America.

Harry Trumbore drawing from The Field Guide to Bigfoot and Other Mystery Primates.

Keep the research alive; please take a moment to…